The Hidden Threat Flowing Through Our Waters: How Potomac Riverkeeper Network Is Taking on Microplastics, PFAS, and Biosolids

When we think about pollution in our rivers, we think of plastic bottles, litter and even tires. But some of the most dangerous contaminants threatening our waterways, and our food system, are largely invisible.

Kayakers on the Potomac River. Photo credits: Potomac Riverkeeper Network

Microplastics, PFAS, often called “forever chemicals,” and biosolids the sewage sludge byproducts of wastewater treatment plants that are routinely spread on farmland and sold to the public as garden products.

At the forefront of confronting these threats in the Potomac watershed, a tributary to the Bay is Potomac Riverkeeper Network (PRKN), a nonprofit dedicated to protecting the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers and the communities that depend on them. Through rigorous testing, policy advocacy, and public accountability, PRKN is exposing how these contaminants move from wastewater systems into rivers, farms, food, and ultimately, our bodies.

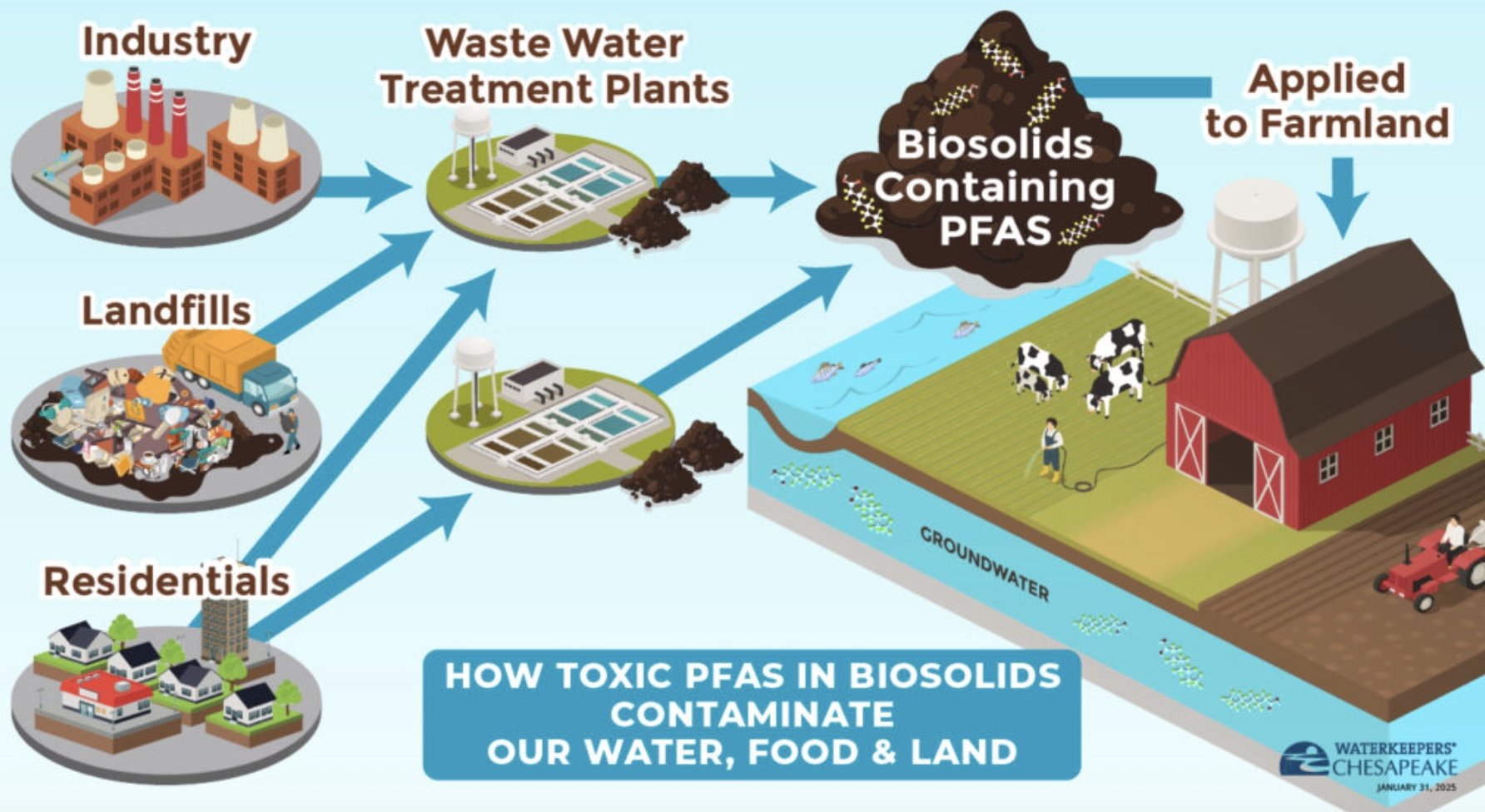

From Wastewater to Farmland

One of PRKN’s most significant recent efforts uncovered something few residents and advocates knew: biosolids produced in Washington, DC and Maryland are being transported across state lines and spread on farms in Virginia, often without farmers’ knowledge of what those materials contain.

After testing biosolids from 22 wastewater treatment plants in Maryland, PRKN found dangerously high levels of PFAS across the board. The findings were so consequential they were ultimately featured in The New York Times, bringing national attention to a regional issue with far-reaching implications.

PFAS do not break down in the environment. Once they enter soil or water, they persist, accumulating in crops, livestock, wildlife, and people. And yet, these contaminated biosolids continue to be applied to farmland across 48 counties in Virginia, including fields that produce food for local and regional consumption.

Biosolids diagram. Photo credits: Potomac Riverkeeper Network

The Potomac, Blue Plains, and a Leadership Gap

The Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant, the largest in the region, plays a central role in this story. While DC Water has been widely praised for its investments in infrastructure and its work to reduce combined sewer overflows into the Potomac, PRKN argues that leadership must extend further.

Blue Plains produces more biosolids than any other facility in the region. Some are classified as Class B biosolids, which are spread on farms. Others are processed into “Bloom,” a Class A biosolid product sold directly to the public for gardens and landscaping. Independent testing by organizations including the Sierra Club has found PFAS in these products.

This raises an urgent question: How can residents make informed choices about what they put in their gardens if they are not knowledgeable about what's in these materials?

As PRKN emphasizes, this is not about dismissing the progress DC Water has made. It is about calling for consistency: if the District aims to be an environmental leader, biosolids and PFAS must be part of that leadership.

PFAS Diagram. Photo credit: Potomac Riverkeeper Network

A Public Health Crisis Hiding in Plain Sight

The consequences of PFAS contamination go far beyond environmental degradation. Across the country, communities are beginning to see the long-term impacts. In Maine, where biosolids were banned years ago, the state has since issued meat consumption advisories for deer due to lingering PFAS contamination in soil. Farmers have lost livelihoods. Families have faced devastating health outcomes, including cancer, despite doing everything “right,” including organic farming.

Closer to home, PFAS runoff contaminates groundwater, enters shellfish populations, and threatens the seafood industry in the Chesapeake Bay region. Watermen, farmers, and families are all affected, often without knowing the source. This is why PRKN frames biosolids not as a niche environmental issue, but as a food system and public health crisis.

A Path Forward

1. Farmers’ Right to Know legislation

PRKN is working in both Maryland and Virginia to require biosolid testing and disclosure at the farm level. Farmers deserve to know whether the materials being spread on their land are contaminated with forever chemicals. And to refuse them if they are.

2. Permit advocacy and accountability

Through public comment campaigns and legal advocacy, PRKN challenges wastewater permits to require PFAS monitoring and reduction. In Arlington, Virginia, for example, community pressure helped generate over 100 public comments, leading to a public hearing on the wastewater treatment plant’s permit and its PFAS discharges.

This work also points toward scalable solutions. Michigan, for instance, has begun regulating significant industrial users, like metal plating facilities and landfills, that send PFAS into wastewater systems. By requiring pretreatment at the source, PFAS levels in biosolids are already declining. A successful model exists and we need political will to implement it in the DMV region.

What You Can Do

PRKN emphasizes that everyday residents have power.

Attend public hearings and submit comments on wastewater permits

Ask questions about biosolid products used in community gardens and landscaping

Support legislation that requires testing, transparency, and PFAS reduction

Learn more through PRKN’s three-part webinar series featuring scientists, lawmakers, and farmers from across the region

Our waterways are not separate from our lives, it flows through our food system, our economy, and our health. To learn more about Potomac Riverkeeper Network’s work on PFAS, biosolids, and water quality, and to find ways to take action, visit their website and follow their ongoing advocacy.